The North-South Rail Link, it's interesting connection to the MBTA Communities Act and Congestion Pricing

NEW SERIES ALERT!

Our Future Bostonia: An in depth look into the Evolution of Boston into a Mid-21st Century City, what it means for our communities and competing public interests.

Every Monday & Tuesday; By Steve Banninger, Architecture and Urban Planning Writer for ExploreBoston.com

If you're an avid newsreader or listener like I am, then you may have thought there was an echo for the past few weeks regarding Congressman Seth Moulton's support of a Rail Link between North and South Station; better known as the North-South Rail Link (NSRL). If you've been a longtime resident of Boston since the Big Dig, then you would probably recall a similar echo since the 90's. If you were a Bostonian in 1919, you'd be confused because two railways already connected North Station to South Station at that time...in addition to being confused about this magic picture and word box you're reading this article on.

What is the North-South Rail Link (NSRL)?

“I live in Salem, Massachusetts,” he said. “I would never take a job on the South Shore because you can’t get there from Salem, certainly not at rush hour. That could be a two-hour trip in one direction. With the Rail Link, it would be about 40 minutes. So it’s totally transformative. You can live on the North Shore and work on the South Shore. You can live in Worcester and get to the Cape on a Friday afternoon in the summer in no time at all, whereas you could be sitting for three hours in traffic. We know how bad that can get. That’s why it’s so transformative and incentivizes so much housing.” Congressman of the Massachusetts 6th Congressional District, Seth Moulton on the Codcast

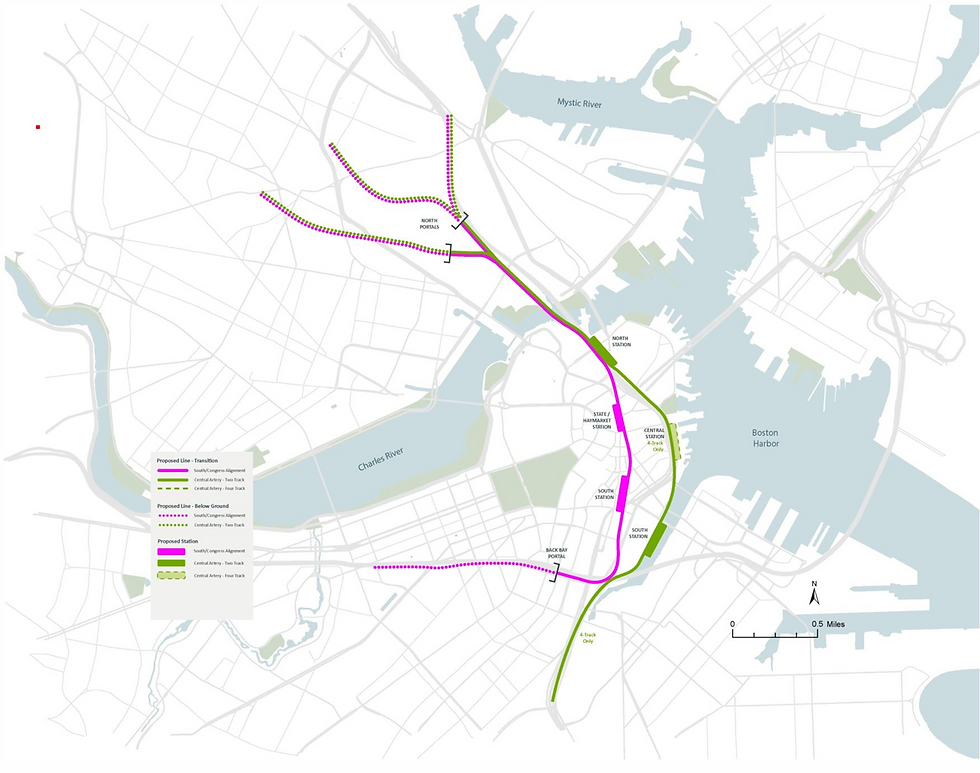

What you're looking at on the left, is the current state of the commuter rail system we have today; while on the right is what the system would look like with the addition of roughly three miles of tunnel under the heart of Downtown Boston linking North and South Station. The project would add a third rail station to Boston, Union Station which would connect MBTA Commuter and Amtrack Lines to the Blue Line Aquarium T Station.

Consequently, according to the Citizens for the North South Rail Link, this would create several new "unified" lines in theory:

Fitchburg- Readville Line

Littleton - Plymouth Line

Lowell- Green Bush Line & connects to cities in New Hampshire & Montreal

Haverhill-Franklin Line & connects to Portland via Amtrack Downeaster Line

Wilmington-Worcester Line & connects to Springfield, Pittsfield, Albany, & Chicago

Newburyport- Cape Cod Line

South Coast-Beverly Depot Line

Rockport-Needham Line

Anderson RTC-Wickford Junction Line & connects to New York, Philadelphia, Washington via Amtrack Northeast Corridor and The Acela

All of these lines would connect to:

Green and Orange Lines at North Station

Blue Line at a new Union Station (Aquarium)

Red and Silver Lines at South Station

Beverly Depot, Anderson FTC, JFK/UMASS, Quincy Circle, Back Bay, Ruggles, Hyde Park, and Readville would become major transfer points between three or more lines

PC: Citizens for the North South Rail Link- Left: A three dimensional map of the link through down town showing the three stations, Right: A plan showing the extents of the project area, Botton: A section showing the link passing under existing tunnels

Historical Context: Downtown Boston Railways in 1919

From 1872 - 1969, the Union Freight Railroad shipped freight traffic between North and South Station servicing the industrial needs of the wharfs. Between 1901 and 1939 the Atlantic Elevated line provided passenger rail service between North and South Station but did not connect to the main rail lines, only to the Washington Street and Charlestown Elevated lines; predecessors to the orange line. This meant you would have to transfer onto the "El" then back onto another train at the opposite station, a "three seat" connection. In 1919 the Boston Molases Disaster damaged the elevated rail, disrupting service for several months. After the opening of the East Boston and Sumner Tunnels in 1904 and 1934 respectively, demand for the line could no longer sustain it's cost to function, especially after a decline in activity at the Warf's and was torn down for scrap metal during the Second World War. A 1926 state report recommended converting the route to an elevated highway, the Central Artery would be built in the 1950s above Atlantic Ave and was destroyed in 2003 by the Big Dig.

Left: Atlantic Ave Elevated passes in front of south station in an early 20th century drawing, Center: Plan of the Original Orange Line, Right: A photo of a sign announcing the accelerated demolition timeline due to World War II

How is the North-South Rail Link a Promise Lost in the Depths of The Big Dig?

"If the Massachusetts economy is going to continue to grow and create good jobs for our people, making that system better must be our top priority," Dukakis and Weld wrote in a Boston Globe Op-Ed in 2015

"My view on this, and said this to both governors, is that when it comes to projects like this, the devil is very much in the details," Baker said. "And while it's not possible, necessarily, to get every answer to every question, because in many cases they're not all answerable all at once, these are projects that should be treated with a high degree of respect and we plan to treat it that way." Governor Charlie Baker said to GBH in 2015

PC: Massachusetts State Archives- Left: Plan showing location of the central artery elevated highway, Center: Plan sowing MBTA lines and proposed rail link with a new "central" station, Right: '93 post-link line proposals

The organization that has produced many of the modern graphics, maps, and plans for the project, Citizens for the North South Rail Link, states in the about section of their website they were, "brought together by former Governors Michael Dukakis, William Weld, and a coalition of advocates from across the region in support of better and more effective, efficient and sustainable transportation policies."

Dukakis ('75-'79,'83-'91) and Weld ('91-'97) were back-to-Back Democratic and Republican Governors respectively, who oversaw some of the most important planning stages of the "Big Dig" Central Artery/Tunnel project. Both ran for President, Dukakis in 1988 losing to George H.W. Bush; and Weld in 2020 for the Republican nomination after Weld was nominated for Vice President on the 2016 Libertarian ticket. The link was initially lost under the Dukakis administration due to funding concerns over expensive ventilation systems for diesel engines and a second time due to President Reagan's 1987 veto of the project due to the rail link. I highly recommend The Big Dig podcast produced by GBH to learn more about the project, which recently won a Peabody award.

Weld, the Republican, created a task force that published a 1993 report in favor of the plan hoping to find favorable conditions under the recently elected Democratic Clinton Administration. The US Senate approved a further engineering and environmental study that, while favorable, stretched onto 2003 during a time when the Big Dig cost overruns became politically untenable and then Governor Mitt Romney, a Republican, formerly put an end to the project, pulling local funding collapsing federal funding support. He eventually went on to lose to President Barrack Obama in the 2012 election and became Senator of Utah in 2019.

Why haven't we already done this then?

"The reality is the project doesn’t work as a linchpin of the state’s public transit system or merit the more realistic 2018 estimated project cost of more than $20 billion. Largely as a result of the 2017 Kennedy School study, MassDOT went back and did a reassessment in 2018. That sober assessment details the complexity and enormous costs involved." State Representative William Straus, Chairman of the Transportation Committee, in a Boston Globe Op-Ed

We know that Governor Mitt Romney pulled funding due to the link's connection with the Big Dig, which cost a little over 8.08 billion dollars to complete a project in a roughly 7.5-mile corridor; spending billions more on the project was an untenable political position, especially on a project involving federal funding for someone with presidential ambitions.

The rail link is a much smaller project in terms of distance covered than the Big Dig projects, 3-4 miles of mostly underground work that can be completed by boring technology and techniques beyond what the Big Dig had access to. Still there is concern and debate over how much the project will cost. According to WBUR Dukakis and Weld claimed the project would cost 2-4 billion when they talked with the Republican Governor Charlie Baker in 2015, most likely understating the costs generated from the 2002 MASS DOT Study connected to the Big Dig projects which were actually estimated in the 3.3-5.7 billion-dollar range. This number was reinforced by the recommendation of a 2017 study by the Harvard Kennedy School on the rail link, "This research finds that the design and construction cost of the Link total is approximately $3.82 or $5.94 billion (2025 dollars) for the evaluated designs (the minimum two-track or maximum four-track builds)."

While the Citizens for the North-South Rail link group which influenced the 2014-2018 link debates frames the project around the four-track option which adds a "Union" Station and offers the most connectivity; alternative two track options are considered alongside this option which will not add the third station and would offer less connectivity in the system. This is important in understanding the 2018 reassessments by the MASS DOT, when the costs for the project spiked to 8.6-9.4 billion for the two-track option and 17.7 billion for the four-track option. It was these reassessments that caused Baker to favor a South Station expansion that was projected to be in the 4.7-billion-dollar range. The cost for the project increases to 12.3-14.4 billion for the two track alternatives and 21.5 billion for the four-track primary version when additional vehicle costs are considered.

It is interesting to note though that the 2018 study does recommend a two-station alternative relying on constructing the stations within the bore diameter to save money. The study does mention, "While the 4-Track alternative slightly improves access to low-income households served (because of connecting the Fairmount Line) and results in slightly less crowding on MBTA bus and subway lines (because of its slightly greater coverage in the bus and subway service area) over the 2-Track alternative, the 2-Track alternative has a higher score because of its lower overall cost."

PC: MASS DOT - A map from the 2018 study showing the recommended alternative 2 track option (green), leaving out the Fairmount and other southern commuter lines and the ideal 4 track option (Green) that adds a new Union station to the city and provides maximum connectivity between rail lines

Important to this conversation is the electrification of the commuter rail system which is costly but should make the stations cheaper by reducing the need for expensive ventilation systems to filter out diesel exhaust. The Rail Vision plan estimates to do this would cost 28.9 billion, 40.7 billion adjusted for 2030 inflation and would result in 964 self-powered electric rail vehicles for the full transformation, Alternative Six, which would get the most use out of the rail link. These changes would also allow trains to come every 15 minutes no matter the time of day at every station. Electrification projects towards this goal are underway, although there is debate about taking the electrification process to the level Alternative 6 suggests, with the other alternatives of the Rail Vison Plan likely to be favored due to lower costs.

So Why was Congressman Seth Multon running around talking about a Central Rail Link this month and What is this going to Cost Us?

“I mean it just makes no sense – the system we have today. So it has to be transformed, and if Massachusetts is ever going to fix our infamous transportation problems, this is the approach we need to take.” Congressman Seth Moulton on the Codcast

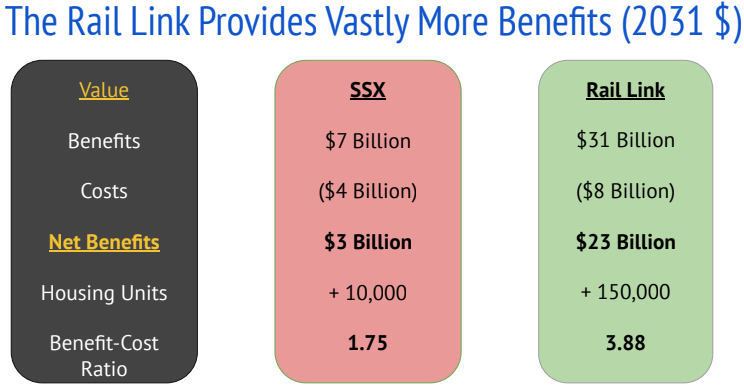

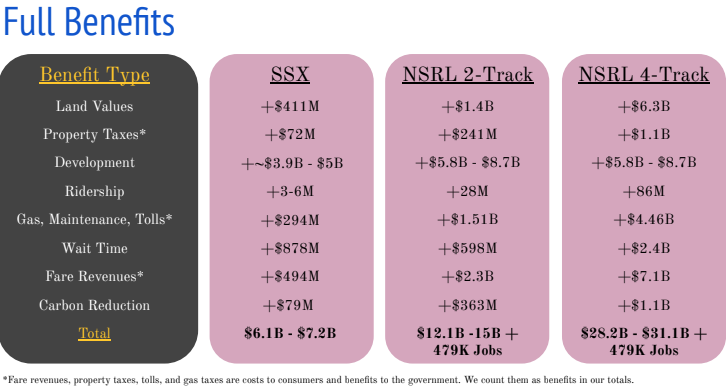

There are a number of overlapping factors for why we're hearing this in the news cycle and why it will continue to be; starting with a recent study conducted by the Harvard Kennedy School into the economic impact and feasibility of the project, so far only the presentation graphics from the study have been released. The upshot, the study found that for spending 7.9 billion on the rail link, we would generate 24 billion in net economic benefits; 31 billion without factoring in the cost of the project which is in dispute.

As of the writing of this article, I myself am confused as to where the Harvad Kennedy School/Congressman Moulton is getting this revised 7.9 billion number from. To reiterate, MASS DOT estimated it would cost 8-12 billion for a severely truncated version of the project (2 track), and 17-21 billion for something the scale that Moulton seems to want (4 track), and the Harvard Kennedy School says it will only cost 7.9 billion to build.

The presentation of the report states, "Costs were estimated both component-by-component using FTA’s (Federal Transit Administration) database of transit projects and by regression analysis of worldwide transit costs using a dataset from the Eno Center for Transportation. The final estimates were triangulated between these models." Now I may not have gone to an Ivy league school, but I can spot that the inclusion of "worldwide transit costs" as the possible culprit as to why the new estimates are low. Mass DOT in their 2018 study did include similar international projects (London Cross Rail, M-30 Tunnel in Spain, and a project in the Netherlands) but also included domestic benchmarks to estimate cost from the Tappan-Zee Bridge, Green Line Extension, Texas Central Rail, and multiple projects in California. It's possible the study assumes that many of the additional costs will be covered by the electrification through the MBTA Rail Vision Plan, but Straus does seem to have valid concerns around if this new Harvard Kennedey School study takes into account permitting for new stations and right of way ownership for tunnels and surface access.

Questions about cost estimates aside however, if we take the most severe estimate for the project, 21 billion, (granted the MBTA's planned purchase of a new battery powered rail fleet may lower this closer to the 17 billion mark) the project will still generate 10 billion in economic benefits to the state, 7 billion more than the project net benefits of the South Station Expansion. Granted the fullest electrification of the commuter rail under Rail Vision could cost an additional 40 billion (adjusted for 2030 inflation while most of these numbers adjusted for 2025 inflation), but the Rail Vision project would generate it's own economic benefits not taken into account by the Harvard Kennedy School and it is unlikely the MBTA will commit itself to the fullest transformation, closer to the 15-25 billion range adjusted for 2030 inflation.

So how does this connect to the MBTA Communities act and Congestion Pricing?

Both of these proposals are massively complicated on their own and deserve their own dedicated articles which I will get to in the future, however the NSRL link...well...links these three proposals together in a very interesting way.

First is congestion pricing which was in the news not too long ago due to Boston City Councilor Fernandes Anderson starting discussions about the prospect, with the matter handed off to the Commitee on Planning, Development, and Transportation. Councilors Edward Flynn and Erin Murphy were the only two councilors not to add their names as co-sponsors to the hearing request. This occurred earlier this year in February, but in June Governor Kathy Hochul indefinitely paused the implantation of congestion pricing in New York citing inflation earlier this month. According to the Boston Globe, "$15 fee be imposed on cars entering Manhattan below 60th Street once per day. The recommendations called for commercial trucks to pay up to $36, and for extra fares on taxis, Uber, and Lyft rides." Low-income residents would have exceptions to the pricing in New York's scheme. Mayor Michellle Wu is still for congestion pricing, in a GBH interview she said that the key to the proposal would be a reliable transportation system that provides alternatives to driving; and she's right.

The idea is that a similar toll would be added to Boston on high congestion corridors, encouraging drivers to either take public transit or modify their commute to avoid peak hours, possibly with the aid of a hybrid remote work model.

While congestion pricing offers a funding option to either increase MBTA funding or replace the gas tax while also reducing automobiles on the road at rush hour; the MBTA Communities act mandates the creation of a multi-family housing district around T stations. The act is very much in the spirit of the NJ Fair Housing Law passed after the Mount Laurel decision, albeit with more of a focus on transit rather than a statewide transformation from exclusionary to inclusionary zoning laws.

PC: Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities- Map showing municipalities affected by the act; Rapid Transit communities (Blue) have the highest addition multifamily housing burden, Commuter rail communities (Blue-Green) the second most with the rest (Green and Yellow-Green) having lower housing requirements

Without the rail link, the MBTA Communities act, in my opinion unfairly mandates housing in a state with a historic issue around properly funding and expand public transit. Many towns, in my opinion are right to question adding people to their communities when roadway capacity already seems pushed to it's limit. Bike and Bus lanes, such as those recently completed on Boylston, can provide new options sure; but with the MBTA Community Act and Congestion pricing, a usable and self-supporting public transit system can be achieved.

In Conclusion, How many times do we need to make the same mistake?

A common theme throughout my research was "getting what you pay for." Nearly all the solutions from the Atlantic Ave Elevated, the Elevated Central Highway Artery, and the Big Dig were limited in the benefits provided to the city because of the lack of a direct link between North and South Station. Any alternative solution that does not guarantee passage of transit riders between North and South station, without transferring trains such as the Old Atlantic Ave Elevated or in the two track alternatives for the NSRL; is not worth even a lower project cost, considering the added time and potential delays multiple transfer's cause. Most riders will begin to seek other modes of transportation if they are forced to transfer more than 2-3 times, so if they need to use one or more bus lines transfers will increase quickly and the system will not be as attractive for riders. We also cannot accept leaving out the historically ignored low-income & blue-collar communities on the Fairmont and Middleboro Lines, who would have to transfer at south station.

Alternative methods explored in a 2018 three team study by the Harvard Enginering School, citied by State Rep. William Straus in his rebuke of Seth Moulton's recent comments, completely ignores this singular fact. Instead, the teams came up with "cheaper" more "efficient" solutions that would still require line transfers to get between North and South Station, their solutions no better than the original Atlantic Ave Elevated which shut down for similar reasons. I'm reminded again of the recommendation from the 2018 MASS DOT study that recommended the two track option; I fear it will be the version selected based on cheapness rather than its effectiveness for commuters. Congressman Moulton and the Harvard Kennedy School may need to revisit their cost estimates for the project; but it would not surprise me to learn that the projected 10-24 billion in economic benefits to the state of Massachusetts ends up being conservative IF we build the four-track option. For nearly a century now, we have had a broken downtown; no matter what the cost is to fix it, don't you want to see the potential of Our Future Bostonia?

Comments