From Daniel Burnham to Paul Davidoff; Our cities and towns have been influenced by figures, relatively unknown to most.

NEW SERIES ALERT!

Our Future Bostonia: An in depth look into the Evolution of Boston into a Mid-21st Century City, what it means for our communities and competing public interests.

Every Monday & Tuesday; By Steve Banninger, Architecture and Urban Planning Writer for ExploreBoston.com

Left Daniel Burnham, Center PC: Cornell University- Pual Davidoff, Right PC: New York World Telegraph and Sun- Robert Moses

To understand Paul Davidoff's assertion that planning is a political process shaped by competing public interests, mentioned in yesterday's article; we first need to explore the origins of urban planning in the United States. The story begins with the 1893 Chicago World's Fair and the White City, a collaborative project led by Daniel Burnham and included Frederick Law Olmsted. This event marked a significant milestone in urban design and planning, emphasizing aesthetics and grandeur.

The White City - The 1893 Chicago World's Fair

In 1871, the Great Chicago Fire devastated much of the city. By hosting the "Columbian World’s Fair" in 1893, Chicago showcased its remarkable recovery and celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage. The fair's centerpiece, the White City, was a collaborative effort by many designers, most notably Burnham and Olmstead but also included Burnham's rival Louis Sullivan.

In Left to Right Order from Top Left: Map of the World's Colombian Exposition, the White City, The Administrative Court Building, Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, The Horticultural building, View of the reflecting pool from Machinery Hall, Louis Sullivan's Transportation Building, 1893 illustration of President Clevland opening the Fair

The fair itself has become infamous being known for the greatest refrigerator fire on earth, incomplete exhibits on opening day, racially insensitive exhibits, funding issues, the first Ferris wheel, the serial killer H.H. Holmes, and a mayoral assassination; it was even featured as a backdrop in Season 2 of Loki on Disney+. There was even a relic from our city, a vial of tea from the Boston Tea Party. The book, The Devil in the White City, captures these legends in a New York Times bestselling book by Erik Larsen and focuses on a juxtaposition between Daniel Burnham and H.H. Holmes.

Burnham's Magnum Opus of a new neoclassical style of uniquely American Architecture, was The White City. Louis Sullivan contributed a polychromatic design for the Modern Transportation building, which departed sharply from the rest of Burnham's vision and was ironically the only piece of architecture discussed in the foreign press. Both men contributed to the Chicago School architectural style, with Sullivan being remembered as the leading influence, while also mentoring a young Frank Llyod Wright who would design Falling Water and the Guggenheim Musem in NYC among other projects. Wright Would later remark of the White City which is mentor's rival created, "By this overwhelming rise of grandomania I was confirmed in my fear that a native architecture would be set back at least fifty years." which echoed similar comments made by Sullivan.

Olmstead's lagoon, plant selection, and landscape design created a natural escape for the energized crowds of Burnham's White City and would inspire the City Beautiful movement aimed at addressing the growing tenement housing districts of America's Gilded Age cities. Later critics of the origins of city planning like Jane Jacobs would argue that the movement was overly concerned with aesthetics at the expense working class people. While the White city was partially disassembled at the end of that fair, with the rest ironically being destroyed in a fire. Olmstead's improvements to Jackson Park would be what remains of the White City to this day. It would put Burnham at the forefront of other candidates in the minds of the Merchant's Club of Chicago when they wanted to commission the 1909 Chicago Plan.

The 1909 Chicago Plan

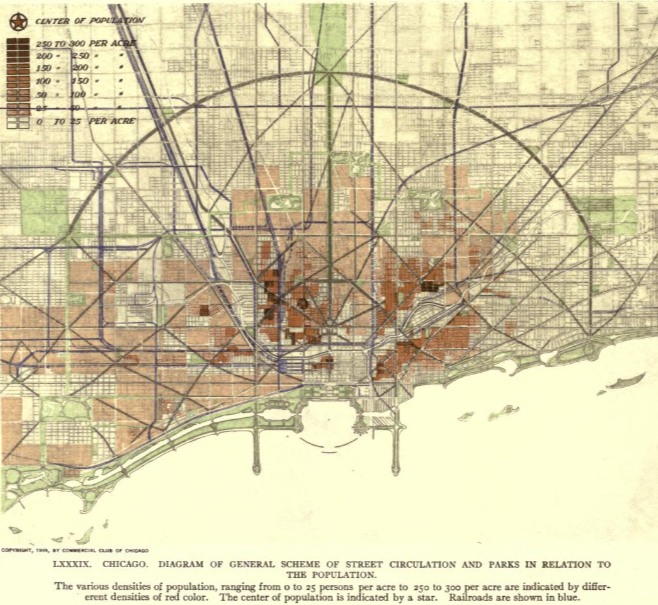

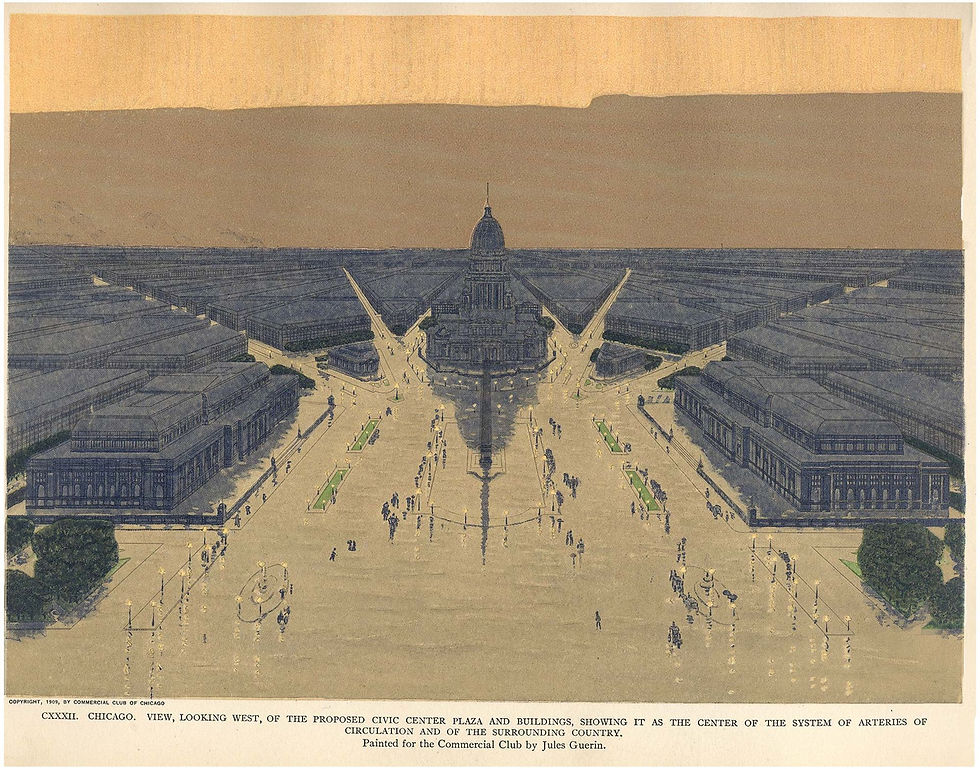

An important document of the City Beautiful movement significantly influenced the emerging city planning profession in the U.S. The plan, developed by Burnham and funded by the Merchant Club and the Chicago Commercial Club, envisioned a new central core, waterfront, civic buildings, and grand boulevards."

The 1909 Chicago Plan however represents an assertion of a unitary public interest, which was funded by two recently merged group of businessmen and was put in front of the City Government of Chicago in 1909 containing mostly physical improvements for the city. This caused the plan to be criticized as an attempt to create a "Paris on the Prairie". Burnham died three years later in 1912, his handwritten list of extensive social improvements that was left out of the plan by the Chicago Merchant Club no longer having an advocate.

The implementation of the 1909 Plan was mostly limited to the Lakefront section, which can be visited today in Chicago. The City Beautiful movement thus emphasized beautification over addressing the social problems of tenement districts.

"Make No Small Plans"

-Daniel Burnham

Ambler Reality Co. v. The Village of Euclid Ohio - The Landmark 1926 Supreme Court of the United States Decision

On the shores of a different Great Lake, sits the Village of Euclid, a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. City leaders and residents were concerned about being consumed by the industrial growth from the nearby city and worried about the village's character. Euclid moved to enact a series of what were being called zoning laws to create six classes of land use based on height and area. These were modeled after the 1916 Comprehensive Zoning Plan enacted in New York City, first of their kind in the nation, to address the housing shortage during a surge of immigration to New York's wide variety of industrial and commercial districts. Ambler Realty owned ~70 Acres of land in the village that it wanted to develop for industrial purposes. Ambler sued based on the fact that the zoning board had reduced the potential profit they could gain from the land; a lower court agreed that this was a violation of what is known as the Taking Clause of the 5th Amendment, 'nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

In 1926, SCOTUS overturned the lower court's decision based on the fact, that zoning ordinance was not an unreasonable extension of the village's police power. Additionally, the case was argued on the basis of the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, "No person shall ... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law," which meant that the law in question would have to show no rational basis; Euclid's zoning ordinance was found to have a rational basis thus establish a nationwide precedent for zoning ordinances.

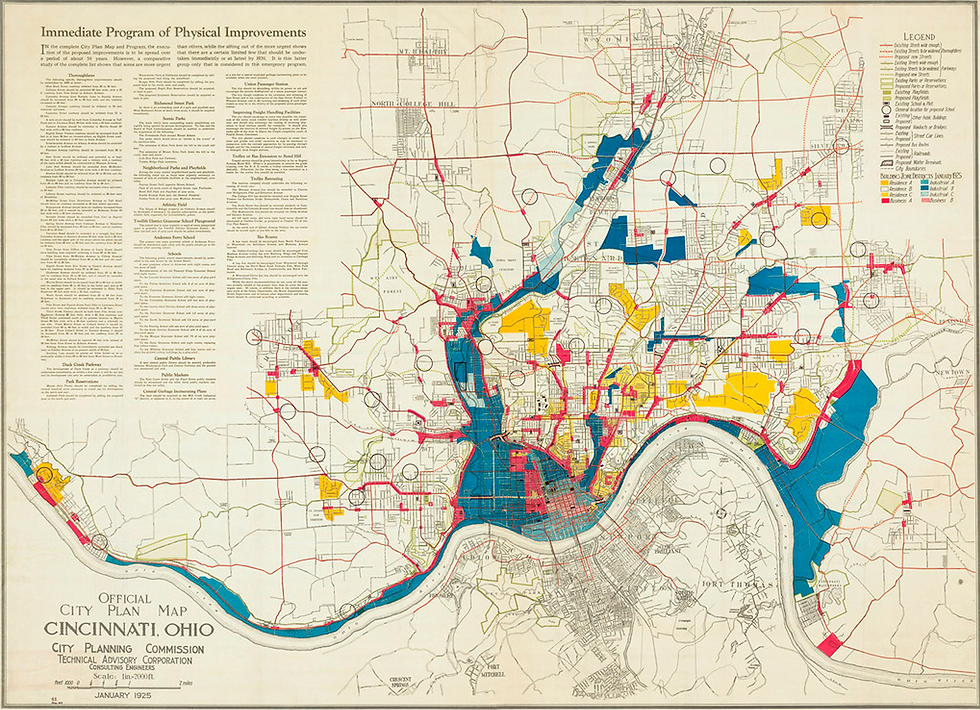

Pivotal to the decision was Alfred Bettman, lawyer and planner, who submitted a friend of the court brief on behalf of Euclid. He was supported by the Ohio Planning Conference, which was founded in 1919, ten years after Daniel Burnham's Chicago Plan. The brief argued that the zoning was a form of nuisance control, therefore a reasonable use of police power. Bettman would go on to popularize the use of the comprehensive plan as a tool for city planning with his 1925 Cincinatti Plan.

The Second World War: Factories, Highways, and the GI Bill

Robert Moses' mother was involved in the Settlement House movement, a reformist social movement that peaked in the 1920s centered around settlement houses where middle income volunteers would live hoping to alleviate the poverty of the urban poor by providing daycare, English classes, and healthcare. The Settlement House, City Beautiful, and the Garden City movements we all active in NYC when the city banned tenement housing in 1901. After authoring an unsuccessful plan to reorganize the New York state government in 1919, Moses gained Governor Al Smith's patronage and was appointed as the President of the Long Island State Park Commission and Chairman of New York State Council of Parks; later appointing him Secretary of State. 1933 saw a high demand of projects from the Works Progress Authority and Civilian Conservation Corps due to New Deal legislation signed by President Franklin D. Roosvelt; Moses had a large number of projects ready to go. A year later, Moses was named Parks Commissioner of New York City, his most powerful and influential position; besides his short stint as Secretary of State of New York.

While Moses transformed New York City with New Deal Funds and centralized planning power; zoning would become the primary way cities and towns defined how land was to be used at a time of great transformation in the rest of the United States. The Ambler tract of land in Euclid, would remain empty until General Motors built an aircraft factory there. With Euclid being a suburb of Clevland, this followed a national trend of factories being built in the suburbs to avoid concentrated bombing by axis forces that fortunately never materialized; except for Honolulu during Pearl Harbor, which was not the main target, nor could the bombing be described as concentrated.

In 1944, the GI Bill was passed creating a range of benefits for soon to be returning soldiers as the war came to a close, notably in housing, education, and employment. To link these new growing suburbs of opportunity, the factories of wartime industrial expansion, and their metropolitan cores; the Federal Aid-Highway Act of 1956 was passed. The President who signed the act into law was Dwight D. Eisenhower who was the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe during the war and advocated for highways after he participated in the 1919 US Army Transcontinental Motor Convoy. For whatever reason 1919 seems to be a recuring year in the behind-the-scenes history of US Urban planning.

During the time these additional funding sources were added to the city planer's arsenal, Robert Moses was appointed city construction coordinator in 1946. For the next two decades he would continue to gain power even to the point of halting the creation of a Comprehensive Zoning Plan while transforming the city with multiple park and highway projects while adding thousands of housing units to the city.

Left PC: New York World Telegraph and Sun- Moses stands with a model of his proposed Battery Bridge 1939; Top Right the Triborough and Hellgate Bridges; Bottom Left PC: NY Parks Department-Map of expressways Moses wanted to build some of which never were or were only partially completed; Botton Right PC: New York Times- Robert Moses stands in front of the Unisphere at the 1964 World's Fair

Like Burnham, Moses would have a national impact contributing to various city plans across the United States. He also gained the support of architects who advocated for an automobile centric form of architecture including Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Moses' power would decline in the 60s and 70s after the beautiful and historic Penn Station was destroyed in a development scheme that Moses was actually not responsible for; Pennsylvania Railroad Company was. He was blamed for the destruction nonetheless due to his association with urban renewal and new development. Combined with the popularity of Jane Jacob's book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, the city population and government turned against Moses' plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway which would have torn through her neighborhood of Greenwich Village and which Jacobs helped to organize resistance to.

After investigations over the funding of the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, which Moses considered his crowning achievement, Moses lost his power after conflicts with Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Moses would lose all of the commissions that had given him his power from 1960-66.

"Cities have the capability to create something for everybody, only because, only when, they are created by everyone." -Jane Jacobs

Robert Moses' legacy would be defined in Robert Caro's The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York in 1974, which won a Pulitzer Prize and was the final nail in the coffin for Moses who was the Special Advisor on Housing to the NY State Governor's Office by then. While Moses' accomplishments were written about in detail, the displacement of communities from the construction of the Cross-Bronx and thirteen other expressways, combined with his insensitivity was fully detailed to the public for the first time. In addition to being against public transit, Moses was also detailed to have racists tendencies highlighted in an incident in which he opposed black World War II veterans entering a housing complex designed for them through programs like the GI Bill; itself having its own issues with discrimination of 1.2 million black veterans. After the book was released, Moses left office by the next year.

“You can draw any kind of picture you want on a clean slate and indulge your every whim in the wilderness in laying out a New Delhi, Canberra, or Brasilia, but when you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax.”

-Robert Moses

The Mount Larel Doctrine and the Metroplitan Action Institute

Paul Davidoff was born in 1930, three years before the New Deal funds that fueled Robert Moses's rise were approved. He grew up in Sunnyside Gardens Queens NYC, NY; the neighborhood was influenced by the Garden City movement a contemporary of the City Beautiful Movement. The goal of the movement was to create satellite communities around a central city that would utilize greenbelts and aim to create smokeless, slum-less cities. After growing up in a New York City under Robert Mose's shadow, Davidoff left for college, eventually getting into Yale Law School but left for the University of Pennsylvania after taking a planning course to purse a planning education there. One of the first major planning projects he was involved in early in his career as a planning consultant was an update of the 1960 New York City Comprehensive Plan, the very same the Robert Moses delayed.

Eventually becoming a professor at UPENN, Davidoff published "Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning" which challenged the Post-War planning profession unquestioned assertion of a unitary public interest. Davidoff suggested that there were multiple public interests, often minority groups, that were ignored by the centralized planning agencies downtown which Davidoff argued primarily represented only downtown development interests. Davidoff challenged the way American planning schools taught the next generation of planners by insisting on the creation of the advocacy planner. He argued that these racial, ethnic, and class interest groups in cities and suburbs should have access to skilled planners who could create opposition plans when central planners came to stabilize and revitalize their neighborhoods. Allowing for a discussion and hopefully a synthesis of the two adversarial plans.

After continuing to impact academia, Paul Davidoff would run for congress in 1968 while a faculty member at Hunter College which he would lose; but he would start the Suburban Action Institute a year later which focused on creating opportunities in the suburbs for poor and working-class families of color.

Since Euclid, what became a tool to protect idyllic suburbs from industrial sprawl also became a tool to exclude households of certain classes, ethnicities, and races. Now named the Metroplitan Action Institute, Davidoff's organization would team up with the Southern Burlington County N.A.A.C.P. to challenge Mount Laurel Township's exclusionary zoning laws in New Jersey. This was after the township announced it's intention to tear down the remaining low-income housing in the community which would displace some sixth-generation residents. Subsequent suits would allow the New Jersey Supreme Court to refine the Mount Laurel Doctrine to create a mandate that municipalities in growth areas provide enough housing opportunities for low and moderate income households. In response to this mandate, New Jersey Legislature passed the NJ Fair Housing Act in 1985, a year after Paul Davidoff passed away due to complications from cancer and four years after Robert Moses passed away

Comments